In their Agility Factor article, Thomas Williams (Booz & Company) and Christopher G. Worley and Edward E. Lawler III (both of the Center for Effective Organizations, University of Southern California), defined ‘agility’ as:

a cultivated capability that enables an organization to respond in a timely, effective, and sustainable way when changing circumstances require it.

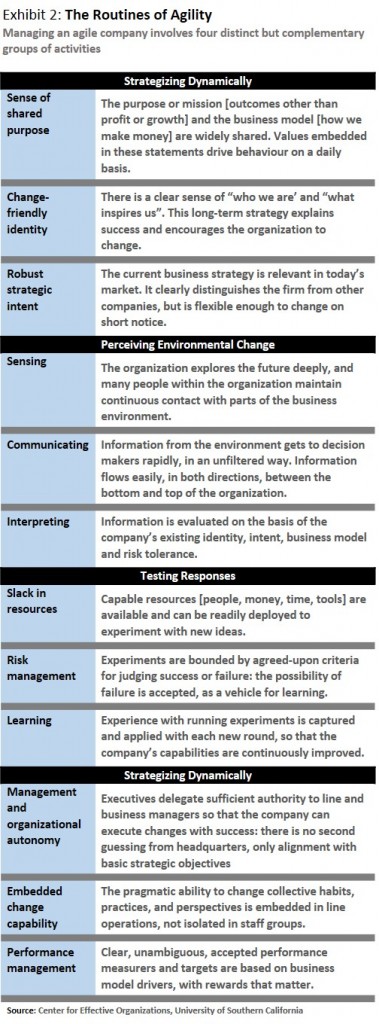

They identified four ‘routines of agility’ that differentiated the high performing organizations: strategizing dynamically, perceiving environmental change, testing responses, and implementing change as outlined in their Exhibit 2 below and discussed in my previous post.

How do these agility routines relate to Adaptive Iteration? I believe that Adaptive Iteration is a way of building and embedding the organizational capabilities and individual expertise necessary to support the agility routines as follows:

Strategizing dynamically

Sense of shared purpose: is incorporated as a key element of Adaptive Iteration. A clear and shared overarching purpose is critical to guide the many Adaptive Iteration decisions and choices. It also provides the high-level scope necessary to enable and stimulate creative and innovative improvement options.

A change-friendly identity: is encouraged and stimulated by Adaptive Iteration. The Observation and Interpretation capabilities embedded in Adaptive Iteration encourage and develop a realistic assessment of the alignment of the organization with its purpose and operating environment. The resultant shared recognition of any misalignment creates the collective tension and energy necessary for constructive change.

Robust strategic intent: is an outcome of applying Adaptive Iteration to the organization’s business strategy. Adaptive improvement approaches, such as Adaptive Iteration, excel in the emergent and partially predictable context of most business strategies. Adaptive Iteration is a fractal capability that can be used not only to change and improve a business strategy but also to stimulate and guide the necessary changes to the organization’s capabilities and resources.

Perceiving Environmental Change

Sensing: corresponds with the Observe phase of Adaptive Iteration. Adaptive Iteration requires, encourages and develops incisive and unbiased observation of all aspects of the organisation and its environment. It provides a framework within which observations (sensing) can trigger adaptive responses.

Communicating: is embedded in the iterative nature of Adaptive Iteration; in the emphasis on multiple perspectives during the Observe phase; in the emphasis on diversity during all phases, but especially Interpret and Design; and in the progressively expanding nature of the Experiment phase. Open communication is embedded in Adaptive Iteration and should grow throughout the organization as a result of its use.

Interpreting: corresponds with the Interpret phase of Adaptive Iteration. Adaptive Iteration recognizes that many situations are an ordered/random hybrid that cannot be analysed with precision or predicted with certainty. However, interpretation of observations can identify important change-related characteristics such as early signs of failure or success, non-linear patterns, key constraints and decision points, and driving influences.

Testing Responses

Slack resources: are made available when adaptive improvement (ie Adaptive Iteration) is recognised and acknowledged as a necessary and routine organizational capability. Embedding a framework such as Adaptive Iteration creates the structures, capabilities and triggers within which ‘slack resources’ can be released and applied. It bridges to the existing discipline and rigor required for operational excellence.

Risk management and learning: are embedded in the iterative nature and emphasis of Adaptive Iteration and in its requirement that all iterations be guided by a clear and commonly understood overarching purpose. The explicit separation of observation, interpretation, design and experimentation reduces the potential influence of biases and predetermined expectations. Adaptive Iteration and its enabling capabilities promote and encourage purposeful learning-based action throughout the organization.

Implementing Change

Management and organizational autonomy: is encouraged and facilitated by the structured and rigorous nature of Adaptive Iteration. Adaptive Iteration is not an ad-hoc or occasional approach to developing and implementing change and improvement. It does not require close management involvement and oversight. Rather, as with the organization’s operational processes, it is a disciplined processes supported by well-defined capabilities and routines and governed by the organization’s overall purpose.

Embedded change capability: occurs when Adaptive Iteration (or any other structured approach to adaptive improvement) is adopted throughout the organization. The clear discipline and structure of Adaptive Iteration is a natural extension of the organization’s operations.

Performance management: arises from the use of an overarching purpose or intent to drive decisions and choices throughout Adaptive Iteration. Care must be taken to ensure that narrowly set performance objectives and measures do not limit creative or innovative options and do not drive the iterations to a premature and sub-optimal conclusion.

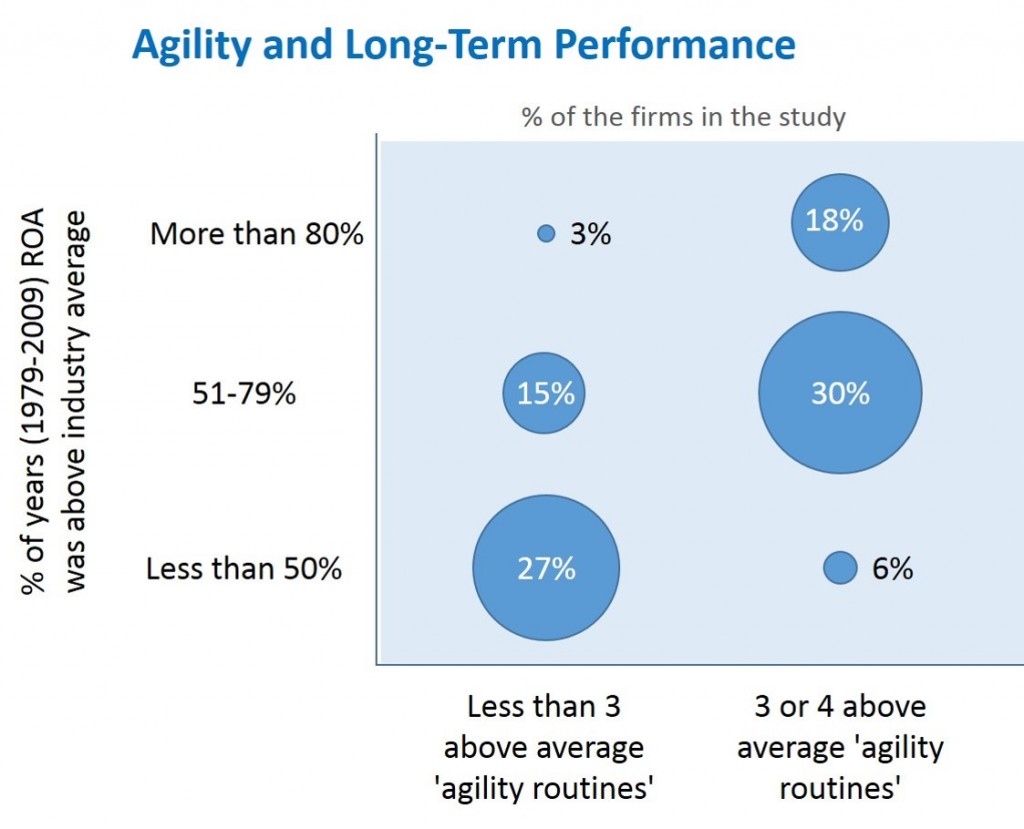

In summary, the work of Williams, Worley and Lawler has highlighted a correlation between organizational agility (as assessed by four agility routines) and company profitability. Adaptive Iteration is an approach to developing organization agility and in this post I have explored how it maps to the four agility routines described by Williams, Worley and Lawler.

Photo: Derek Jensen – Wikimedia commons

In general, we need to adopt perspectives that allow us to be more empirical. That is, we need to focus on more extensive observation and data gathering before drawing conclusions. In most cases, we also need to recognise that the conclusions are only hypotheses that require further testing and validation. We need to be open to revising, or even discarding, a hypothesis as we make more observations or collect further data.

In general, we need to adopt perspectives that allow us to be more empirical. That is, we need to focus on more extensive observation and data gathering before drawing conclusions. In most cases, we also need to recognise that the conclusions are only hypotheses that require further testing and validation. We need to be open to revising, or even discarding, a hypothesis as we make more observations or collect further data.

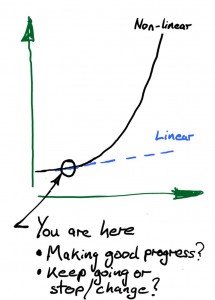

Why is non-linear behaviour so interesting and important? Because it is helps explain why certain situations change so rapidly and unpredictably. What might appear to be just small inconsequential changes or random ‘noise’ may in fact be the early weak signs of success (or failure). We may think that our new initiative is not working and prematurely abandon or significantly change it. Alternatively, we may see quick success and commit further resources to an initiative or change effort only to find that it expectedly slows down or stagnates. A deeper awareness of the nature and types of non-linear behaviour will sensitise us to the potential for these types of situations and help us look for indicators of non-linear patterns and mechanisms. It will also help us set expectations accordingly.

Why is non-linear behaviour so interesting and important? Because it is helps explain why certain situations change so rapidly and unpredictably. What might appear to be just small inconsequential changes or random ‘noise’ may in fact be the early weak signs of success (or failure). We may think that our new initiative is not working and prematurely abandon or significantly change it. Alternatively, we may see quick success and commit further resources to an initiative or change effort only to find that it expectedly slows down or stagnates. A deeper awareness of the nature and types of non-linear behaviour will sensitise us to the potential for these types of situations and help us look for indicators of non-linear patterns and mechanisms. It will also help us set expectations accordingly.

Follow Us!