We are conditioned to see what we expect or are primed to see, not what is really there. This is fast and efficient if our world is stable and predictable where the past is a good predictor of the future. But what if it is unstable and unpredictable? What if our expectations and experience are only partially useful? The problem is that our expectations and experience are often deep within our subconscious mind. It is difficult to switch them off even if we consciously realize they may be inadequate in a given situation.

We are conditioned to see what we expect or are primed to see, not what is really there. This is fast and efficient if our world is stable and predictable where the past is a good predictor of the future. But what if it is unstable and unpredictable? What if our expectations and experience are only partially useful? The problem is that our expectations and experience are often deep within our subconscious mind. It is difficult to switch them off even if we consciously realize they may be inadequate in a given situation.

How then do we see things as they really are, not as our subconscious would like or expects them to be? One of the most effective things we can do is to develop the ability to step through a variety of perspectives when examining a situation. In doing so we use our conscious brain to counter or supplement our subconscious brain.

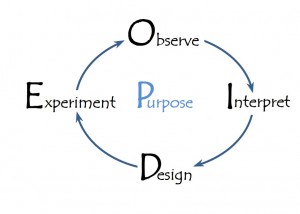

In general, we need to adopt perspectives that allow us to be more empirical. That is, we need to focus on more extensive observation and data gathering before drawing conclusions. In most cases, we also need to recognise that the conclusions are only hypotheses that require further testing and validation. We need to be open to revising, or even discarding, a hypothesis as we make more observations or collect further data.

In general, we need to adopt perspectives that allow us to be more empirical. That is, we need to focus on more extensive observation and data gathering before drawing conclusions. In most cases, we also need to recognise that the conclusions are only hypotheses that require further testing and validation. We need to be open to revising, or even discarding, a hypothesis as we make more observations or collect further data.

I have categorised the various perspectives we can take under four broad categories – spatial, structural, psychological and effectual.

Spatial perspectives

Get close to the action to see actual behaviour and events rather than make assumptions based on past, prescribed or ‘normal’ behaviour. This approach underpins the Genchi Genbutsu (“go and see”) principle of the Toyota Production System.

Move further away from the action so that you can see behaviour and events in a wider context (draw wider system boundaries) and therefore consider more structural influences and factors. Moving further away is also likely to increase detachment and objectivity and therefore reduce any biases introduced by an emotional engagement to the situation. The movement need only be psychological (for example, by imagining you are in another city), not necessarily physical.

Divide the situation into a comprehensive set of segments and examine each of them separately and then the relationships between them. This approach reduces the risk that your focus quickly narrows on those aspects that you expect or assume to be the most salient. It ensures that all aspects get at least some focused attention. The segmentation basis could be physical, organisational or temporal (time based).

Examine the behaviour at the boundaries of the system or within the system. New or changing influences and behaviours will often be first evident at the boundaries. This is either because new external influences first interact with system at the boundaries, or because the more diverse interactions that occur at the boundaries generate new ideas and options.

Structural perspective

Consider the network aspects of the system or situation. Are there any groupings or networks emerging? If so, what are the ‘attractors’ for the groupings, or what is driving the linkages for the network? Is there potential for these to be self-reinforcing, or are there likely to be fundamental constraints to their ongoing development? On the other hand, what are the established networks and groupings? Are they structured to facilitate or inhibit positive change?

Identify the constraints in the situation. The constraints may relate to physical boundaries, information, expertise, resources, awareness and expectations. If behaviour consistently occurs at or near a constraint, the behaviour is unlikely to change without first relaxing or modifying the constraint.

Look for any potentially significant decision points. Major decisions create ‘forks in the road’ that influence the future development of the system or situation. At the personal level, they include choice of a partner, a profession/career, a place to live, etc. At the organisational level, these decision points are numerous and diverse and may not seem particularly significant initially. However, they may stimulate or facilitate a self-reinforcing chain of events that eventually have game-changing impact.

Identify any emerging patterns of cause and effect. Even though the situation appears essentially unpredictable, repeatable cause and effect patterns may be emerging. Customers in a given segment may have begun to respond more predictably to on-line promotions. Middle managers from one segment of the organisation may be exhibit similar resistance to a change initiative and offering suggestions for improvement that have a common underlying theme. These emerging patterns provide early indications of what is working and what is not. They provide potential guideposts for future action.

Behavioural/psychological perspectives

Look at the situation through the eyes of the key participants. In other words, take a perspective of empathy. Aspects of the situation that may be clear and positive to you may be unclear, uncertain and therefore threatening to some of the participants. Benefits of a change initiative that you think are valuable may appear to be of marginal value when seen through the eyes of a stakeholder group.

Identify the dominant motivations and influences in the situation. Look for the ‘why’ as well as the ‘what’? Where do the energy and driving forces for action come from? Are they derived from proactive aspirations or reactive defensiveness? Is the source local or broadly based? Is it likely to be enduring or short term? In emergent and unpredictable situations, the driving influence is a potential source of consistency and coherence. Although it will not enable future decisions and outcomes to be predicted with certainty, it will point to how they are likely to be biased.

Is the situation characterised by a few dominant emotions? Emotions have a fundamental influence on behaviour and decision making. We may be able to bring some clarity to what appears to unpredictable and illogical behaviour when we understand their emotional underpinning. Looking at a situation through a lens of emotions may provide insights that we may find it difficult to discover otherwise.

Effectual (effects and results) perspectives

Notice what seems to be working. Where are successes happening? What activities and behaviour are being reinforced? Where are people making progress in spite of their constraints and context? What have they done to overcome the constraints? Is this repeatable and scalable? In unpredictable and emergent situations we cannot rely primarily on what has worked in the past or has worked somewhere else. We need to discover new principles for success.

Be alert to the surprising and the unusual. Often, much ‘information’ is found in the unexpected events, behaviours, relationships and achievements. These may be weak signals of the emergent direction of the situation, or they may be just random noise. If it is random noise, and the surprise is a positive one, can the random conditions be identified and repeated consistently? The earlier the small surprises can be identified, the more likely it is that they can be purposely enhanced if they are positive or suppressed if they are negative.

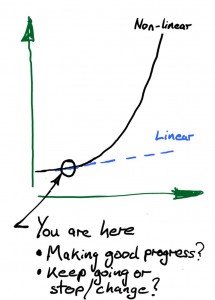

Why is non-linear behaviour so interesting and important? Because it is helps explain why certain situations change so rapidly and unpredictably. What might appear to be just small inconsequential changes or random ‘noise’ may in fact be the early weak signs of success (or failure). We may think that our new initiative is not working and prematurely abandon or significantly change it. Alternatively, we may see quick success and commit further resources to an initiative or change effort only to find that it expectedly slows down or stagnates. A deeper awareness of the nature and types of non-linear behaviour will sensitise us to the potential for these types of situations and help us look for indicators of non-linear patterns and mechanisms. It will also help us set expectations accordingly.

Why is non-linear behaviour so interesting and important? Because it is helps explain why certain situations change so rapidly and unpredictably. What might appear to be just small inconsequential changes or random ‘noise’ may in fact be the early weak signs of success (or failure). We may think that our new initiative is not working and prematurely abandon or significantly change it. Alternatively, we may see quick success and commit further resources to an initiative or change effort only to find that it expectedly slows down or stagnates. A deeper awareness of the nature and types of non-linear behaviour will sensitise us to the potential for these types of situations and help us look for indicators of non-linear patterns and mechanisms. It will also help us set expectations accordingly.

Follow Us!